Part 1: Too Many Messiahs

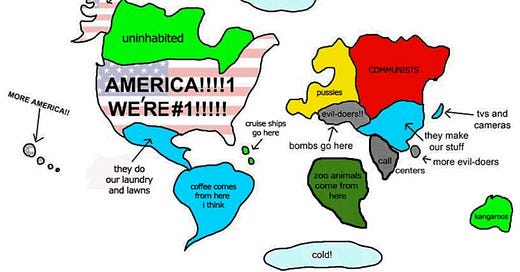

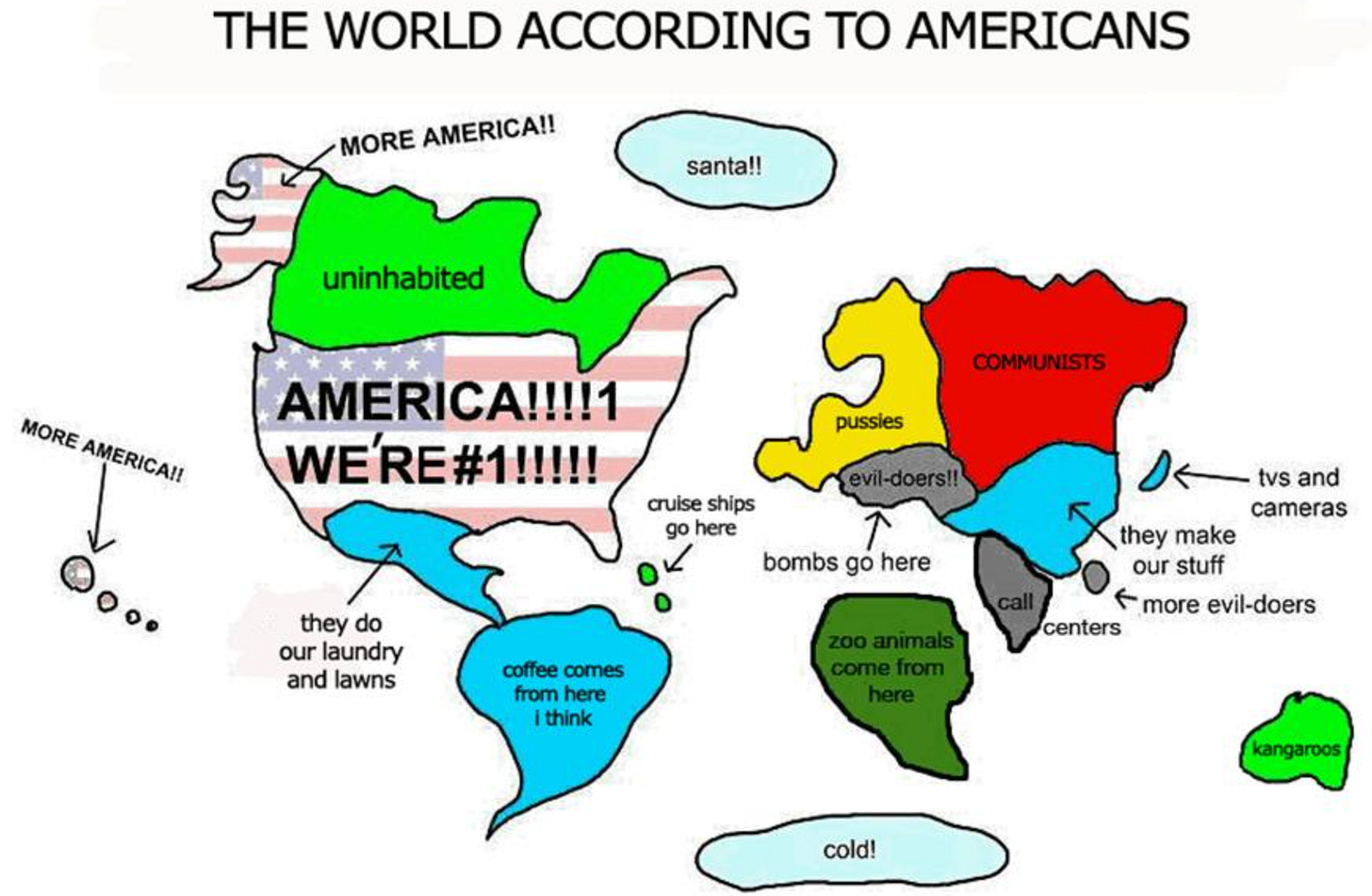

There is an old stereotype of Americans that we view the world like this.

I heard this view of Americans a lot while living abroad. The stereotype isn’t entirely wrong, but, in defense of my fellow yankee doodles, we have 330 million people, and we obviously don’t have our crap together, so just keeping up with everything we need to know about ourselves can be exhausting. Trying to learn about the rest of the world when we have a fire hydrant of news about our own country and state(s) is difficult. Some people might say that’s not a good excuse, and maybe it’s not, but ordinary people don’t sit around waiting to absorb every drop of policy or current events they can find. Most people just want to work their job, and come home to watch football or the Bachelor and spend some time with their family or their friends. Knowing less about politics doesn’t make these people less important.

Christians have a similar view about history.

It goes something like this. Jesus was definitely the Son of God, and definitely paid for everyone’s sins, making Christianity the one and only religion of truth approved of by God (we’ll stay away from the discussion about which Christianity is the one and only, because that’s a minefield the we don’t need to step into for this reasoning to make sense). Because of this, all religious history prior to 30(ish) CE was clearly and obviously pointing and leading to the Atonement performed by Jesus. Any religious history not obviously proto-Christian must have been a corruption by evildoers. Therefore, all religious history should be understood through this proto-Christianization of history.

If we follow that logical trail, it’s not an entirely illogical conclusion. It just turns out to be incorrect.

The result of this is the creation of a “history bubble” that Christians tend to live in, where everything is viewed through the lens of their faith. There is nothing wrong with that, as long as their faith doesn’t exclude factual evidence—but sometimes it does.

It also causes some serious harm. This type of mindset is ripe for manipulation from real life evildoers who might want to convince someone to, say, kill all the Jews. If Jews ruined God’s one true religion, then murdered God(‘s only Son) because they corrupted God’s religion, then Jews kinda seem like bad people…don’t they?

Understanding history this way also limits or excludes some pretty amazing religious insights and can lead to the marginalizing of some really important Galilean Carpenter teachings. This three part series is an attempt to explain just one of those that sometimes gets marginalized by modern Christians.

Christians know the words in the Bible really well. But, Christians by and large tend to know very little about the Bible. Inside this Christian history bubble the Old Testament is not the Hebrew Bible, it’s the obvious prelude to the sacrifice of Jesus. How could any Jew read the Old Testament and not know that Jesus was the Messiah!?!?!?!?!

Well if religious history is understood outside of the Christian bubble, then it’s never obvious at all the Jesus was the Messiah.

To begin with, the idea of a messiah is widely misunderstood in the Christianized world. A messiah is simply one who is anointed. Moses’ brother Aaron appears to have been the very first messiah (Exodus 30). Throughout all of the history of Israel and Judah it appears the king of each kingdom was usually anointed a messiah. But, this kingly messiah was not singular—there was also a second, priestly messiah. When the Hebrew Bible talks about a messiah, it should be understood in these terms.

So, how did we get to the point where the whole Jewish world was awaiting a messiah? And how did the early Jesus movement come to believe Jesus was this person? For that we have to go way back to the beginning of written history.

It’s hard for us to imagine now, but for the majority of human history the idea of an existence after death has not been the norm. Egypt in the ancient world seems to have been somewhat of an outlier with its focus on the afterlife.

Briefly:

In Babylon, the wise bartender in the Epic of Gilgamesh describes the common Babylonian belief in the afterlife—that this life is really all we have, and death is the ultimate end so we should enjoy our life and make the most of our time with loved ones.

In Greece, circa 800ish - 700ish BCE, The Odyssey describes Odysseus speaking to the great hero Achilles in Hades. Achilles tells him that being a slave on earth is far preferable to being the ruler of Hades. Hades isn’t so much an afterlife as it is a coffin. It’s where spirits go to rest in an eternal coma, because death is really the end.

In ancient Israel Sheol is somewhat similar to this eternal coma belief of Hades.1 When a spiritual medium brings Samuel back from Sheol to consult king Saul it smells a lot like Odysseus and Achilles. Samuel really doesn't have much to say to Saul, and leaves him to his fate.

It’s not until 400(ish) BCE that we start seeing people like Plato really develop the idea of an eternal soul separate from the physical existence. Plato describes Socrates telling his students to not to be sad about his death sentence because Socrates tells them that through death he is going home.

It is around this time—400ish BCE—that the afterlife begins to play a big role in human thought.

It’s important to note, at this point, that I’m leaving out a major player—Persia. Sometimes it seems like history forgets Persia existed as we focus on Greco-Roman history. But Persia was a BFD for thousands of years. Condensing some major history into one sentence: Assyria annihilated Israel, then Babylon annihilated Assyria and went on to conquer Judah, then Perisa annihilated Babylon. Persia let the captive Jews go back to Jerusalem, and they seem to have adopted some Persian thought into their spiritual id.

In Persia Zoroastrianism—at that point a relatively new religion—was introducing some pretty new ways of thinking about God and existence. The faith introduced dualism to the Jews: the idea that the world was a struggle between good and evil forces.

Prior to this, the concept of a satan in Israel and/or Judah was not the evil god-devil Satan is now. Rather, satan simply means something along the lines of "one who opposes", and a satan in the Hebrew Bible seems to really be working for/with God as a prosecuting attorney, not against God as an enemy.2 The book of Job is the perfect example of this. Satan is working for/with God to prosecute the case of faith and obedience among humans.

Side Note: The book of Job has a lot of Christianized translation. Someone reading this might object to the history by citing the “redeemer” passage in Job. At first it may look like Job believes in an afterlife where he will be treated justly. But the word redeemer—goali in the original—just refers to a kinsman who is responsible for you after your death. More like the executor of a will than a Christ figure. Job believes this person will make his case as a sort of defense attorney so his legacy isn't one of an evildoer punished by God. Job 14 is really all about this finality of death.So, the idea of dualism is born. This leads to the Pharisees, who believe in a resurrection of the dead, and that God will establish an afterlife kingdom of the righteous here on earth. But, more on this later.

I’m gonna make historians really mad and recklessly condense a lot of history into a few sentences to save time and get back to the main point. After the Jews return from Babylon they are never really in charge of themselves for quite a long time. For a couple centuries they are still a Persian vassal. Then some guy named Alexander, who was pretty great, comes along and conquers the Persians. He died young and his empire got divided up. Israel gets bounced around between Greek rulers for another couple centuries. During all of this time the Jews had no messiah. Their temple was desecrated a few times, and they never ruled themselves.

Then something pretty cool happened. A Jewish guy named “the Hammer” started a war against the Greeks and won. This eventually started the Hasmonean dynasty in Jerusalem, and the Jews ruled themselves. They had a messiah—an anointed king— again. The party was fun while it lasted, but before long Rome became, well, Rome. Judea stopped being a kingdom and became a Roman vassal.

This time period (200ish BCE to year 0) is when the idea of what THE3 Messiah would be developed. The Messiah came to be understood as, and modeled after, the successful Maccabean revolution. The Messiah would conquer all of Israel's enemies and once again establish the kingdom of God on Earth. This was not the spiritual sort of thing we think of now. As Jews thought of themselves as God's chosen people through the promise made to Abraham, any independent kingdom of Israel would also be considered the literal kingdom of God.

The Messiah was a long awaited and long promised king who would use military might and prowess to defeat not only Rome, but anyone who would challenge Israel—much like the Maccabees had done—and restore Israel to the once great nation its history taught that is was in the time of Messiah David. In order to be The Messiah a man had to be a warrior, like David was.

Now, let’s get back to that good versus evil thing, and the development of THE4 Satan. By this time Plato had revolutionized thought, and Jews had become fairly hellenized. The dualistic struggle between good and evil forces to control the world was also all the rage. Life had not been great for the Jews for hundreds of years; they kept getting conquered, they were a relatively minor player in the world, and they had nowhere near the wealth and grandeur they expected to have given God's promises. The reason, they came to believe, had to be The Satan. The cosmic evil force was responsible for all their woes; after all, they were good people who kept the Law of Moses, so it couldn't be God who was punishing them. Around this time it appears The Messiah also came to be understood as would also conquer all evil. The Satan would be defeated and the literal Kingdom of God would be established where the good God would finally crush the evil cosmic force.

After the successful Maccabean revolt, there was no shortage of people who thought they were definitely The Messiah during Roman rule. Josephus details about a dozen of them. It’s interesting stuff. The Essenes, who may be the group that wrote the Dead Sea Scrolls, and may have come from the Qumran movement, were so sure their righteousness would bring in the “Teacher of Righteousness” who would be The Messiah, and restore Israel.5

Right around the time Jesus was born there were three significant would be messiahs—Judas of Galilee, Simon of Perea, and Athronges (I should note that Jesus’ birth was not the catalyst for these three, rather, it was King Herod’s death). All of them were violently put down by the Romans. The Zealots and Sicarii were perhaps the world’s first terrorists, and thrived in the anti-Roman sentiment in Galilee. The Temple of Jerusalem was destroyed because of another would be messianic revolt about 40 years after Jesus died. There was still another, yet bloodier revolt after this that led to the permanent ban of Jews from Jerusalem. All of these would be messiahs failed.

In fact, someone claiming to be The Messiah was so common in Jesus’ time that it may have even been written into the New Testament. Barabas, which may translate to “son of the father”, is most likely a fictional character, but we are told he “was in prison with the rebels who had committed murder during the insurrection.” (Mark 15:7, emphasis mine) It’s unclear what insurrection this was supposed to have been, but first century readers were familiar enough with the concept of insurrections against Rome by messianic figures that the author of Mark knew it would serve as a useful juxtaposition in the peaceful narrative of Jesus.

Messiahs were everywhere in Roman Judea. All of them failed to meet the expectation of The Messiah as understood by the Jews from the Hebrew Bible and Jewish tradition. Interestingly, some of these would-be messiahs seem to fit prophesy from the Hebrew Bible better than Jesus did. Archeologists have even found a third day resurrection narrative about a would-be messiah who predates Jesus.6 It's not clear who this refers to, but Simon of Perea seems to be a decent fit.

The bottom line is Messiahs were a dime a dozen in Jesus’ time. There are two clear lessons to take away from this:

First, Christianity is not just the logical continuation of Judaism, or the correction of the “true” religion started by God in the Garden of Eden then corrupted by humans. This is one way to read history, and it is a reasonable way to do so, but this should not be seen as a given. It is fully and completely reasonable for Jews to read the Hebrew Bible and not come to the conclusion that Jesus was The Messiah. Ask a Rabbi about this sometime, it will be an interesting conversation if you keep an open mind. Judaism is a beautiful faith in and of itself, don’t hate on Jews.

Side Note: I'm not making any commentary on what you should or should not believe. It can be possible both that Jesus was The Messiah, and that the Hebrew Bible does not point to him as the expected Messiah. Nothing I have written here should damage anyone's faith in their respective religion.Second, the Bible must be understood in its context. Knowing the words of the Bible alone is not enough. Parts 2 and 3 of this series will explain why American Christians often miss out on some beautiful theology and faith because of this Christian history bubble.

Political messiahs are also a dime a dozen in the United States. There is a laundry list of Republican candidates who have run for president because God told them to. Rick Santorum, Michele Bachmann, Mike Huckabee, Scott Walker, Sarah Palin, Ben Carson, Rick Perry, and Mike Pence… and that’s just off the top of my head. (We’ll ignore the awkward subject that many of these candidates were apparently told by the same God to run against each other in the same election.)

Even someone as blatantly unChristlike as Donald Trump was a Messiah—it even seems like most Republicans view(ed?) him as THE7 Messiah. I spent several dozen pages in my book on this exact subject.

Why?

Because Christians are trying to build the kingdom of God.

Christians have read into American history the same beliefs they read into the Hebrew Bible—that all of American history is pointing toward the day when this will be a Christian nation. Some mistakenly believe the United States was founded as a Christian nation, and has since lost its way. So, every time a messiah comes along, white evangelicals flock to him (and it has always been a him, despite Bachmann’s and Palin’s attempts to change that) hoping that he will be the one. Like Jews awaiting their Messiah, Christians hope that this political messiah will overcome the evil Democrats and pass all the laws that Jesus wants—that this can finally be a nation modeled after their Jesus.

I hope you’re enjoying this letter so far. You can subscribe to make sure to catch every edition of The Constituent. It’s completely free!

Part 2: Too Many Peters

Jesus had some really interesting followers. But, that’s sort of to be expected given that Galilee was full of insurrectionist anti-Roman types. We’re told Simon was a Zealot (Luke 6:15), which was a radical band of revolutionaries that wanted to start a war with Rome. James and his brother John were called “sons of thunder” (Mark 3:17) and wanted to rain down fire to destroy a village that wasn’t as welcoming to Jesus as they’d have liked(Luke 9:54). Judas Iscariot might have been a sicarii8, which were assassins named after the type of knife they used. This idea comes from his name Iscariot, which is pretty similar to sicarii, even more so when it's not in English. Sicarii were not really a big deal until after Jesus’ death, so the history is questionable. But, since nobody really knows what Iscariot means, and the gospels weren’t written until the time sicarii were a big deal, it’s a reasonable interpretation given the other company Jesus kept.

Then we have Peter. His given name is Simon, but he is also given the title “the rock”9 by Jesus—Petros in Greek, or Cephas in Aramaic. Christians tend to just use the Greek, so we call him Peter.

Peter isn’t given a title of a revolutionary, but there is no question that is who he was. In the very conversation where Jesus names him The Rock, Peter has to be rebuked by Jesus. Jesus is explaining how The Messiah will have to suffer and die to fulfil the messianic calling, and Peter suggests Jesus should never suffer or die. In this rebuke, Jesus even calls Peter satan—remember from part 1, this just means one who opposes—and chastises him for “setting your mind not on divine things but on human things” (Matthew 16:23). Jesus is telling his closest followers that anyone who doesn’t think Jesus should suffer is opposed to his mission. It’s pretty remarkable.

But Peter doesn’t get it.

How do we know Peter doesn’t get it? Well, think about part 1. Would-be Messiahs were everywhere in first century Judea. The traditional expectation of all the Jews was that the coming Messiah would be a military hero who conquered Rome and all of Israel’s enemies, just like the Maccabees had done to the Seleucids. The cultural understanding of what a Messiah must be was framed by the most recent messiahs from the Hasmonean dynasty. Peter thought this is who Jesus was. And, from a careful reading of the four gospels, this seems to be who almost all of Jesus’ closest followers thought he was. This is so clear, when a careful reading is done, that many New Testament scholars come to the conclusion that Jesus even thought of himself as a traditional messianic figure, and later interpretations wrote the spiritual Messiah into the narrative after Jesus’ death.10

For Peter it was the logical response to contradict Jesus. He objected, “God forbid it, Lord! This must never happen to you.” (Matthew 16:22), because if Jesus were to suffer and die he could not be The Messiah as Peter understood it.

When Jesus actually does suffer, and the Temple Guards come to arrest him, Peter still doesn’t understand who Jesus is, and takes out his sword and cuts off the ear of Malchus, the High Priest’s servant. What Jesus tells him is remarkable, unless we understand that Peter thinks he is following the traditional Messiah.

Put your sword back into its place; for all who take the sword will perish by the sword.

Do you think I cannot appeal to my Father, and he will at once send me more than twelve legions of angels?

It’s worth noting that 12 legions of angels would dwarf the number of Roman soldiers in the entire province, and probably the entire area. But Peter still wants to fight because he doesn’t understand who Jesus is.

Why was it that “Then all the disciples deserted [Jesus] and fled”, and Peter denied Jesus three times (Matthew 26:69-75)? Because Josephus tells us that Rome crucified over 2,000 Jews after the failed revolts after the death of King Herod. Rome never took kindly to the followers of insurrectionists—and Peter thought that’s who Jesus was.

After Jesus dies, and even after Peter has seen him resurrected in the Gospel of John(!), what does Peter do? A resurrected Jesus appears in John 20, and as soon as Jesus is gone, “Simon Peter said to [the other disciples], ‘I am going fishing.’ They said to him, ‘We will go with you.’” (John 21:3). Peter, and several other disciples went right back to being fishermen because they still didn’t understand who Jesus was.

The non canonical Gospel of Peter makes this even more clear. Jesus’ closest followers mourn his death for about a week in Jerusalem (Jesus does not appear to them), and then Peter decides the messianic dream is over, and he gives up and goes fishing.

Side Note: It might seem odd that Peter goes fishing in John after seeing a resurrected Jesus. As John was the final gospel written of the four in the New Testament, this appears to be an attempt to square the accounts of Matthew and Mark with that of Luke. In Mark and Matthew—the two earliest Gospels—Jesus appears only to Women in Jerusalem, and tells them he will meet the other disciples in Galilee. Luke—written after Mark and Matthew—has Jesus appearing in Jerusalem, and telling the disciples not to leave Jerusalem. The Gospel of Peter follows the earlier tradition that Jesus did not appear to his disciples until they were in Galilee. The Gospel of John appears to attempt to harmonize these two traditions.To Peter, and many of the other 12, Jesus was just another failed dime a dozen messiah. They thought Jesus was The One, and then he died. He was just one more person to excite their passions about a holy war that would set in motion the promised Kingdom of God. It wasn’t until after the day of Pentecost that they finally seemed to get it.

Why did they miss the mark so badly? Because they had been too consumed with tradition, and had insisted the scriptures must mean what their tradition said they meant.

Perhaps my favorite story in the whole New Testament takes place in the final chapter of Luke. Cleopas and an unnamed disciple are leaving Jerusalem. On the road to Emmaus they are joined by an incognito Jesus, who pretends to be ignorant of the events of the previous week. They explain the events to Jesus, and express their sadness that the messianic mission ended in failure. Then Jesus walks them through the Hebrew Bible. He interprets the scriptures a new way, a Christian way, explaining that The Messiah was always supposed to be a spiritual Messiah; a Messiah to conquer sin and death, not a Messiah to conquer Rome.

After the two disciples finally recognize Jesus they ask each other, “Were not our hearts burning within us while he was talking to us on the road, while he was opening the scriptures to us?” (Luke 24:32). And this was the key. If Jesus really was The Messiah, then they had misunderstood the scriptures, and expected Him to be something He was not. That realization is the key to all of Christian history.

There is an amazing phenomenon in Conservative American Christianity. After many brave people dedicated their lives, and even gave their lives in some instances, to translating the Bible into common language, and making the Bible itself available to the masses, many Christians have reached a point where this sacrifice doesn’t do them any good. Rather than taking this amazing book that many give their life for, and reading and thinking deeply about its meanings, they just allow their pastor to tell them what the Bible means. This was exactly the practice that people like William Tyndale and John Wyclif fought to prevent—clergy being the ultimate religious authority, and the sole source of Biblical knowledge. What good does it do for Christians to have a Bible, then interpret it only as they are told to by the leaders of the church. They never seem to entertain the possibility that their religious leaders might be wrong—just like the religious leaders in Jesus day were wrong.

Instead, everyone is a Peter. Quick to violence, eager to start shooting, and reacting rather than thinking. If a Peter cannot achieve their version of the Kingdom of God in the voting booth, they storm the Capital and try to assassinate those they believe are working against them.

Too many Steve Bannon and Alex Jones types, like Peter, are quick to declare a messiah, quick to call to arms, quick to use their verbal swords to cut off the ears of their enemies, and quick to abandon their messiahs when their own necks are on the line. Democrats are Rome, moderate Republicans are the traitorous Jewish elites who cozy up to Rome to remain in power. They must be defeated for God to succeed.

Like Peter, these people know what they understand to be the Kingdom of God must be right around the corner. Peter was wrong about Jesus. These modern day Peters are just like the original—the fact that they might be wrong never enters their mind. These Peters, in their quest to feel like they are serving God and trying to establish the kingdom, forget that God could use legions of angels if he wanted. God doesn’t need these Peters.

Having fun? Learning something new? If so, do me a favor and let your friends know about The Constituent.

Part 3: Definitely Not Enough Marys

After being 180 degrees wrong about who Jesus was, Peter eventually came around to understanding Jesus. Apparently all it took was spending 50 days with the resurrected Jesus, and the outpouring of the Holy Spirit at the day of pentecost.

But even this may not have gotten Peter fully to the right place. Paul’s vocal and pointed disagreements with early church leadership show that even after the pentecost, Paul still had to pull them toward what Christians understand to be God’s doctrine today.11

Early Christian writings that weren’t included in the Bible tell us Peter still had to be pulled along by another disciple—Mary Magdalene.

To understand this, we first have to understand who Mary was. It’s common understanding that the title Magdalene simply means that she is from Magdal. But on closer examination, this doesn’t quite fit. In first century Judea, and even in the Bible, designation origin is different from a title. I mentioned a couple in part one: Simon of Perea, and Judah of Galilee. Of course we know about Jesus of Nazareth, but in the Bible we also have Joseph of Arimathea and Mary of Bethany.

On the other hand Luke introduces Mary called Magdalene (Luke 8:2). I don’t want to bore you with details in Greek, but the only times the “called” word is used (that I can find) it is used in naming someone or something, not in detailing the origin. Most of the time she is just referred to as Mary Magdalene. This is noteworthy because this follows the pattern of other titles given in the New Testament. Simon the rock (Peter), Thomas the twin (Didymus), James the Just, Simon the Zealot, James and John the sons of thunder. Often times “the” is just left out, like with Simon Peter, Jesus Christ, Thomas Didymus, and Mary Magdalene.

So, why would Mary be given the title Magdalene? Because the word means “Tower”.

Mary the Tower.

To better understand why this name is so significant I need to briefly explain research from Elizabeth Schrader. But honestly, she’s amazing—Schrader is getting her PhD in early Christianity at Duke—and a brief explanation doesn’t do her work justice, so you should go read it. When she was studying the oldest known copy of the Gospel of John she noticed something strange. In John Chapter 11—where Jesus raised Lazarus from the dead—the oldest known copy of John had been visibly altered. It could actually be seen that someone named Martha had been added to the story. In the oldest known copy of John, the original told only of Lazarus and his sister Mary. Mary’s name had been changed to Martha (Greek Iota changed to Theta) or Martha had been added in other places.

Why is this significant? Because in the entirety of the New Testament only two individuals actually figure out who Jesus is: Peter—who turned out to be wrong (read part 2)—and Martha. If Martha was added, then it was Mary who actually knew Jesus was the Messiah!

I won’t walk you through the rest of Schrader’s research, because you should read it, but it’s pretty clear that Mary Magdalene is the sister of Lazarus. Mary the Tower is the disciple who really knew who Jesus was.

Think about Mary Magdalene’s role in the New Testament for a minute. Simon the Rock abandons Jesus, Mary the Tower is at the cross. Mary the Tower is the first to go to the empty tomb after the sabbath ends. Mary the Tower is the first to see Jesus resurrected. Mary the Tower is the only person to declare Jesus to be the Messiah, and be right about what that means.

Think about the anointing of Jesus—an act necessary in order for a man to become a messiah. Who anoints Jesus as the Messiah? Mary. Remember, we’ve already discovered that Mary Magdalene was Lazarus sister—Mary and Lazarus of Bethany. Matthew and Mark don’t name the woman who anoints Jesus, but we know they are in Bethany. In John Lazarus’ sister Mary—whom we now know to be Mary the Tower—anoints Jesus.

Side Note: The event in Luke seems to be earlier in the ministry, not in Bethany, and the woman is not named, but is hinted to be a prostitute. She also does not anoint Jesus' head, an act required for the anointing of a messiah. John again appears to be attempting to harmonize the disagreement.Maybe she misunderstood like Peter, but given that Peter abandoned and denied Jesus, then went fishing, and Mary stayed as close to him as possible, it seems she had it right.

Early Christian writings not included in the New Testament strengthen this claim. In the Gospel of Philip Jesus loves Mary more than the rest. In the Gospel of Peter Mary is referred to a as the disciple of the Lord (emphasis is mine). In the Gospel of Thomas Jesus will do whatever is needed to make sure Mary gets into heaven. In Pistis Sophia Peter complains because Mary is the favorite disciple, and he feels like she gets more time with Jesus. In the Gospel of Mary Jesus tells her things he doesn’t tell the other apostles.

The bottom line is this: in many early Christian traditions, Mary rivals or surpasses Peter for importance. Mary knows who Jesus really was, and it is because of her that the other Apostles come to see the plot clearly—she helps them understand what Jesus had to help Cleopas understand on the road to Emmaus. Then, history writes her critical role out of the story. In the oldest copy of John we have, she is literally altered or replaced.

But she is not the only remarkable Mary. Mary Jesus’ mother also never abandoned him. Throughout his life, when Jesus was doing miraculous things, she didn’t see him like Peter saw him. Instead, “His mother treasured all these things in her heart.” (Luke 2:51)

Martha being added in John does not delete the Martha in Luke. Instead these are two different stories, and we have a third amazing Mary. When Martha is busy doing what tradition tells her she should be doing—preparing for and hosting guests—her sister Mary is instead sitting at Jesus’ feet, learning. Jesus tells us this was the better choice—to break tradition and learn something new (Luke 10:42).

Conservative Christianity needs more Marys. More people who think deeply about their faith. More people who are happy to buck tradition if it means being closer to Jesus. More people who are willing to look at their faith from a radically different angle instead of relying on tradition passed on by religious leaders.

Jesus does teach to “seek the king of God and his righteousness first” (Matthew 6:33), but what does this mean? Peter thought it meant a political kingdom, and he was wrong. Many conservative Christians seem to think they are called to build a political kingdom. Mike Pence and Mike Pompeo are among a group of Christians trying to start war with Iran because they think a nuclear holocaust would usher in the return of Jesus. How does that square with the philosophy of loving one’s enemies, and being a good neighbor like the Samaritan, and all the pacifism of Jesus. Jesus rebuked Peter for using violence, even when Peter was doing so in an attempt to establish (what he wrongly believed to be) the kingdom of God. Why is violence even on conservative Christians’ radar?

How then, should the kingdom of God be built? It’s simple. Love.

But, just about any non Christian will tell you, Christians are known less for love, and more for but love. What is but love?

I love black people but, I don’t want them to (insert stereotype here).

I love immigrants but, I just wish they would (insert stereotype here).

I love Muslims but, I’m just afraid that (insert stereotype here).

The list could go on and on.

This isn’t love…at least, not how Jesus described it.

How did Jesus describe love? Like the prostitute that washed his feet.

She went out of her way to do something that was uncomfortable and embarrassing, at her own expense, without tooting her own horn, and opened herself up to ridicule from religious leaders in order to make someone else’s life better. That is what Jesus identified as love (Luke 7:47). That is why her sins were forgiven. The Samaritan caring for an enemy at his own expense, and at the risk of his own safety is what Jesus called love. Peter cutting off Malchus’ ear was not love.

Even Peter eventually came to understand that “love covers a multitude of sins” (1 Peter 4:8) because “The kingdom of God is not coming with things that can be observed; nor will they say, ‘Look, here it is!’ or ‘There it is!’ For, in fact, the kingdom of God is within you.” (Luke 17:20-21, emphasis mine)

Christians build the Kingdom of God by doing the next right thing. Open a door for someone. Smile and say hello to a stranger. Visit a lonely person. If the only way somebody can know that you are a Christian is by your bumper sticker, you are not a Mary. If the only way somebody can tell you are a Christian is when you tell them, you are not building the kingdom of God.

Jesus taught his followers to focus on the means, and let the ends take care of themselves (Matthew 6:34). Focussing on the end—the victory against Rome—is what Peter did. A focus on the ends is what Mary the Tower helped Peter the Rock unlearn. The Marys focused on the means. The Marys did the next right thing. No matter how small, no matter how meaningless, the kingdom of God is built by doing the next right thing, and letting tomorrow worry about tomorrow. Rome was not conquered by the sword, it was conquered by Christians being pacificts; by Christians obeying the law; by Christians doing the next right thing. They never tried to take over Rome, and then Christianity took over Rome.

This should be the pattern for Christianity in the political world today. Don’t focus on building the kingdom of God through some grand measure of conquest in American politics. Let politics take care of itself—the nation was righteous enough to defeat slavery, defeat the Third Reich, and defeat Jim Crow before Jerry Falwell put conservative Christians on a political crusade. A wise student of history would note that, despite some short lived victories, the crusades accomplished next to nothing.

The United States doesn’t need Christianity’s next political messiah. The kingdom of God doesn’t need Christianity’s next political messiah. We don’t need any more Peters.

The United States needs more people, especially in office, who will just do the next right thing—even if they lose an election.

The United States needs more Marys.

Johnston, Philip. Shades of Sheol: death and afterlife in the Old Testament. InterVarsity Press, 2002.

Pagels, Elaine H. The origin of Satan. Vintage, 1996.

The use of this word in this way should not be considered in any way to be a copyright infringement on the OHIO STATE UNIVERSITY.

Dito

Stuckenbruck, Loren T. "The Legacy of the Teacher of Righteousness in the Dead Sea Scrolls." In New Perspectives on Old Texts, pp. 23-49. Brill, 2010.

Knohl, I., 2011. The Gabriel Revelation. In The Dead Sea Scrolls and Contemporary Culture (pp. 435-475). Brill.

Ok, fine. At this point I am just mocking the buckeyes.

Eisenman, Robert H. James the Brother of Jesus: The Key to Unlocking the Secrets of Early Christianity and the Dead Sea Scrolls. Penguin, 1998.

Not to be confused with Dwayne “The Rock” Johnson.

A. Ehrman, Bart D. Jesus: Apocalyptic prophet of the new millennium. Oxford University Press, 1999.

B. Ehrman, Bart D. How Jesus became God: The exaltation of a Jewish preacher from Galilee. HarperOne, 2015.

C. Allison, Dale C. Jesus of Nazareth: millenarian prophet. Fortress Press, 1998.

D. Hendricks Jr, Obery M. The politics of Jesus: Rediscovering the true revolutionary nature of Jesus' teachings and how they have been corrupted. Image, 2006.

Tabor, James D. Paul and Jesus: How the apostle transformed Christianity. Simon and Schuster, 2012.