The Uniquely American Problem with Policing

By now I think everyone is aware of the haunting end of Tyre Nichols’ life at the hand of five Memphis police officers. Here is some footage of the murder incident, and be aware; if you have a sensitive stomach, you might not want to watch it. It looks a lot more like a gang assault than it does actual policing.

Well, by international standards anyway.

The biggest problem with this incident is that it, at least among American police, looks a lot like what criminal justice advocates would just call ordinary policing. And this is the issue. Policing in the United States is often more similar to gang behavior than it is to policing in our peer nations.

Often the blame is misplaced on racism within police forces. This isn’t to say racism isn’t a problem among police: it is. Police are more likely to hold racist and racially inequitable views than the general public,1 and the problem runs so deep that even officers of color are guilty of racial bias.

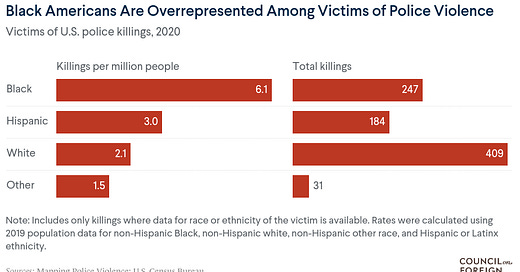

Massive racial disparities are clear in policing and in police violence. You might have heard your far right wing friends try to defend police when they kill black men by citing a study that says white people are more likely to be shot by police.2 The problem is that this study didn’t measure the thing it claimed to be measuring,3 and the authors have retracted it.4 The conclusion only came from the authors misunderstanding their own conditional inferences.

The truth is that people of color are more than three times as likely to be killed by police.5 Even beyond this, white people killed by police were more likely to be classified as “suicide by cop” scenarios, making selective use of force even more disproportionately weighted against people of color. Because minority officers can also have serious implicit bias, hiring more minority officers doesn’t actually fix the problem of violence against minorities.6

But the fact that all five of the officers seen beating Nichols are black demonstrates that the problem runs far deeper than racism alone. Racism and racial inequity are not unique to the United States, but this type of police violence certainly is.

And this is despite the fact that many of these peer countries spend more money on policing than the United States does.

These high profile police killings make it harder for police to do their jobs: it creates a tendency for other officers to back away from policing while on the job, and it makes civilians less likely to trust police officers with complaints and reports.7

While racism is itself a massive problem within policing, it is not the distinctly American problem. Our unique problem with policing falls pretty much into two categories. First, American police do not have enough training, and the training they get is terrible. Second, there are insufficient mechanisms for holding police officers accountable.

Police Training is Terrible

Given the racial disparities in policing and police violence, it might lead one to think that the problem with training surrounds a lack of anti-racism training or racial sensitivity training. This might make sense, but it isn’t the case. Implicit bias training hasn’t been shown to be effective in changing behavior,8 and not just with regard to police officers.9 The policy solution seems to be much more simple than addressing something psychologically complex, like implicit bias. Simply put, in the United States, law enforcement do not receive enough education; they do not receive enough training; and the training they do receive is likely to lead to more violence, not less.

I know I have thrown a lot of academic studies at you for this discussion, and I’m gonna keep doing that so you can see the strength of the evidence for these issues. But to highlight the first issue—the lack of education—I want to tell you a personal story.

A few years back I had a conversation with someone who was in active duty law enforcement; on the front lines of policing and enforcing laws at the state level. A third person who was with us mentioned something they had heard on the radio about racial discrimination in the criminal justice system. The officer shot down the idea that there was any racial bias in law enforcement at all. He insisted that he knew his to be the case because he had taken a training which used data from the FBI’s Uniform Crime Reporting Program, and the data showed that white people were more likely to go to prison than black people.

I was more than a bit confused, because I have used that data several times when doing actual research for clients in government offices or agencies. The data showed no such thing. In fact, it showed the opposite—that there were very real and very persistent racial disparities in both policing and criminal justice. I pointed this out, and even pulled up some of the data to demonstrate this. I thought the data was clear. Actually, let me rephrase that; the data was absolutely clear in showing racial bias. The response I got was one of those things you hear that just makes you stop dead in your tracks.

The officer looked at the data and said, “see, more white people in jail than black people.”

The officer had conflated level numbers with likelihoods or per capita measurements. I politely explained (I don’t remember what the numbers were at the time, so I’ll use the 2021 numbers for reference) that the racial disparity is clear because even though white people made up 49% of the jail population, they were about 75% of the US population. Black people, which only make up 13%-14% of the US population, were 35% of the jail population, and this disparity is similar for other minority groups of color. The officer was unable to understand the difference, and still insisted that white people were more likely to go to jail. The conclusion, in his mind, was evidence that there was no racism in policing.

This officer had not had enough education to understand the concept of likelihood or probability. Now, this isn’t unique to police, many people in the US really don’t understand probability, but I think most could grasp this basic concept that eluded the officer. Here was a man charged with enforcing the laws of his state who did not have enough education to interpret basic percentages. Yet, the state somehow found him qualified to carry a badge and a gun, and to make decisions about when and how to enforce its laws. I was blown away. It seemed clear to me that this officer did not have the intellectual tools necessary to make the difficult penal judgements he was employed to make.

As it turns out, this is fairly common in the United States. Very few police departments in the United States require a college degree. But this has impacts far beyond police lacking what ought to be basic understanding of criminal justice concepts. It’s been known for years that police officers with a bachelor’s degree are far less likely to use force, including deadly force.10 They are also far less likely to engage in misconduct,11 and generate fewer civilian complaints. All of this will, by nature, lead to more trust in police officers by the general public, and save taxpayer dollars on things like lawsuits--perhaps even enough to pay higher salaries to attract more officers with a bachelor's degree.

Without a college degree, you might think that law enforcement agencies work hard to provide the proper training for their officers. You’d be wrong. American officers spend a lot less time training than their foreign counterparts. But the amount of time spent training is only part of the story. The type of training given to officers is entirely counterproductive. If you don’t feel like reading a bunch of stuff, but want to learn more about it, I cannot recommend this podcast enough.

Police are too often trained in the warrior mindset. This training convinces officers that everyone is out to get them, and every situation is a threat to their lives. The biggest issue here is that this type of training creates problems because it escalates situations, increasing the likelihood of violence. Beyond these obvious flaws, the claim simply isn’t true. Being a police officer is a really safe job. Safer than many other blue collar jobs done by other people with similar education levels. The idea that people are waiting around every corner to kill a cop is just not supported by the data.

This problem gets compounded further because it emphasizes doing more of the wrong training. US officers spend less time doing training, get bad training when they do get training, and as a result, spend more time practicing firearm skills than any other type of training.

Firearm skills are obviously critical for officers, but is it necessary that they spend roughly 9x more hours practicing shooting than they do in ethics and integrity training? 6.5x more than in professionalism training? 4.5x more than in communications training? 45% more than in constitutional or criminal law training or basic patrol procedures? Given the data that contradicts the idea that being a police officer is terribly dangerous, I think the answer is obvious.

If the mindset is that everyone is a threat, then black children like Tamir Rice and black community servants like Philando Castile become thugs before they are ever encountered. Then, a toy gun becomes a weapon, and someone with a concealed carry permit becomes a threat—reaching for a wallet become reaching for a gun.

Inability to Hold Officers Accountable

These problems don’t get better because police get to police themselves. The majority of the time police use violence, the entire issue is handled internally. The exception seems to be when video appears showing the truth about what actually happened. Without video proof, officers often flat out lie in their reports, then the police department flat out lies to the public about what happened.

This behavior is similar to what economists see from monopolists. Now, there isn’t really a good way to introduce competition into policing, but there are good ways to enforce behavior. Without good behavioral enforcement we can expect the police to keep behaving like monopolists. In the United States we often foolishly expect companies to self regulate. This leads to disastrous results, because without sufficient competition, there is no disincentive to cutting corners.

I’ve written a lot about how Elon Musk kept manipulating markets to grow his wealth. Boeing was allowed to self certify safety, and planes fell out of the sky. Wells Fargo was allowed to self-police illegal transactions and account creation by their employees, and they kept doing similar stuff. If police get to be their own accountability unit, their behavior won’t change. If the government wants to end anti-competitive economic behavior, C-Suite people should go to jail when they break the law—fining a company won’t work. If police departments want to end violent behavior, officers should go to jail when they break the law—a fine or lawsuit won’t work.

This is really difficult in the United States because police unions expend enormous amounts of resources defending bad police. Derek Chauvin, the man who murdered George Floyd, had a long and ugly history of using excessive force and violence. Every time—until his behavior was caught on camera—his union and the internal investigations permitted him to continue with his terrible job performance. This is actually born out in the data: when problem officers are kept on the force they grow more likely to engage in harmful behavior.12

These protections are further heightened by qualified immunity—the idea that officers get special protection when they are in the line of duty, even if they have committed a crime.

A third complicating factor makes it even harder to hold officers accountable. The person who might charge an offending officer is often the local prosecuting attorney. These attorneys need the help of police when prosecuting civilian criminals; if police are angry about charges placed against one of their colleagues, they can choose not to be cooperative when the attorney is prosecuting other criminals. This makes the community less safe, and if the prosecuting attorney is in an elected position (most of them are), police failing to cooperate can lead to an impossible reelection campaign.

The deck is stacked so heavily in favor of bad cops that the only time we seem to get any police accountability is when clear and obvious footage emerges of their behavior—footage so clear and obvious even the union can’t stand behind them.

At the end of the day the problem won’t change until bad cops know that breaking the law means they will end up in jail. Body cameras are becoming increasingly common, and for good reason. The more video we have the more easily bad police can end up in jail. But there are also other reforms that can be made to remove additional barriers to accountability.

First, firm policies about what happens when body cameras “malfunction”. This doesn’t need to be a one size fits all, but something like a three strike policy might help. If an officer uses any force—deadly or not—or receives a complaint about force, and the body camera is not active, three strikes means they lose their job. This leaves room for honest mistakes by good officers.

Perhaps the best way to hold officers accountable is to take the accountability out of their hands. Civilian Oversight Boards can operate like jury duty; random assignment of citizens to review complaints against officers. If the oversight board recommends criminal charges, an independent counsel gets hired to bring those charges so a local prosecuting attorney doesn’t have to worry about their relationship with the police force. Now, because other officers and public officials in partnership are not involved, the union is limited to the standard representation other unions give their members. They don’t become the gatekeeper against accountability they too often serve as now.

Hopefully you’ve noticed that none of the solutions to either the training problem or the accountability problem are terribly complex. This isn’t taking on an ambiguous monster like ending racism. It would be great if racism could be ended, but I’m not aware of how this could be done. Racism hasn’t been eradicated in other countries, but their police don’t cause the same number or type of problems as police in the United States. Basic steps can be taken to improve policing in the United States, and that isn’t just good for the communities, it’s also good for the police.

Thanks for reading The Constituent. If you’d like to support the newsletter, here are a few options.

-Thanks,

Roscigno, Vincent J., and Kayla Preito-Hodge. "Racist cops, vested “blue” interests, or both? Evidence from four decades of the General Social Survey." Socius 7 (2021): 2378023120980913.

Johnson, David J., Trevor Tress, Nicole Burkel, Carley Taylor, and Joseph Cesario. "Officer characteristics and racial disparities in fatal officer-involved shootings." Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 116, no. 32 (2019): 15877-15882.

Knox, Dean, and Jonathan Mummolo. "Making inferences about racial disparities in police violence." Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 117, no. 3 (2020): 1261-1262.

Cesario, Joseph, and David J. Johnson. "Statement on the retraction of “Officer characteristics and racial disparities in fatal officer-involved shootings”." (2020).

DeGue, Sarah, Katherine A. Fowler, and Cynthia Calkins. "Deaths due to use of lethal force by law enforcement: Findings from the national violent death reporting system, 17 US states, 2009–2012." American journal of preventive medicine 51, no. 5 (2016): S173-S187.

Nicholson‐Crotty, Sean, Jill Nicholson‐Crotty, and Sergio Fernandez. "Will more black cops matter? Officer race and police‐involved homicides of black citizens." Public Administration Review 77, no. 2 (2017): 206-216.

Cheng, Cheng, and Wei Long. "The effect of highly publicized police killings on policing: Evidence from large US cities." Journal of Public Economics 206 (2022): 104557.

Smith, Robert J. "Reducing racially disparate policing outcomes: is implicit bias training the answer." U. Haw. L. Rev. 37 (2015): 295.

Hagiwara, Nao, Frederick W. Kron, Mark W. Scerbo, and Ginger S. Watson. "A call for grounding implicit bias training in clinical and translational frameworks." The Lancet 395, no. 10234 (2020): 1457-1460.

Rydberg, Jason, and William Terrill. "The effect of higher education on police behavior." Police quarterly 13, no. 1 (2010): 92-120.

White, Michael D., and Robert J. Kane. "Pathways to career-ending police misconduct: An examination of patterns, timing, and organizational responses to officer malfeasance in the NYPD." Criminal Justice and Behavior 40, no. 11 (2013): 1301-1325.

Harris, Christopher J. "Problem officers? Analyzing problem behavior patterns from a large cohort." Journal of Criminal Justice 38, no. 2 (2010): 216-225.