Monopolistic Market Failures and Gas Prices

My last letter about gas prices was a lot more popular than I expected. Thank you for that, and thank you for the feedback.

Since the people apparently like to learn about gas policy—at $5 a gallon I guess it’s a BFD—I’m coming at you with a part 2ish. I try to write these letters with enough economic detail that there is an opportunity to really learn something new, but short enough that you don’t need a graduate degree to digest it all. Sometimes that means leaving out some of the more technical economics to A) keep you from falling asleep, and B) keep these letters slightly shorter than a textbook.

Last letter I left out the concept of price sensitivity (economists call this elasticity, if you really want to let people know you’re a nerd), but there was so much interest in the oil market that we’re gonna jump in it with this letter. If you fall asleep, well, you asked for this.

Elasticity is a fancy name for how much you change your buying behavior based on price. At $4 per Schtubben you might be willing to buy 10 per month, but if the price goes up to $6 per Schtubben, and you decide to only buy 5, then you are fairly price sensitive to Schtubbens. Economists would say Schtubbens are relatively elastic. But if you normally buy 10 Musgrots per month at $4, but still buy 9 per month at $6, then you are not really that price sensitive to Musgrot. This would mean a Musgrot is relatively inelastic, and whatever it is, it must be pretty nice for you to want it so badly.

Now, think about a product that everybody buys, and that really isn’t price sensitive for anyone. When this happens it can cause a market failure. Yes, a market failure is a thing, and it is part of basic economic theory. Even economists admit the markets can’t solve every problem, no matter how much Ron Paul insists they can.

The best example of this is healthcare. Here is a thought experiment.

Suppose your kid needs new shoes for a sport they play. How much are you willing to spend on those shoes? 10$? $25? $80? $150? At some point, I’m gonna get to a number where you are gonna think, “shoes aren’t worth that much, no way I’m buying that, especially for a kid who will grow out of them.” And that’s completely reasonable.

Now, suppose your kid was born with a genetic defect that will, 100% guaranteed, kill them. But, scientists are awesome and they have developed a pill that treats this genetic condition. All you have to do is give your kid this pill once a month and they are 100% guaranteed to live a perfectly normal life. Now, how much are you willing to spend on that medication? If I started naming prices, I don’t think I could get to a price where you decide this medication isn’t worth it.

This is called perfectly inelastic demand. No matter what the price is, you are gonna buy that medication. A lot of healthcare has really inelastic demand, maybe even perfectly inelastic, which is why it creates a market failure. Because of this, healthcare does not have to follow any of the patterns of supply and demand.

Perfectly inelastic demand is not the only way to create a market failure due to price insensitivity. As long as a product is fairly inelastic a monopoly or an oligopoly can create a market failure if the cost to start a competing company is too high to expect a reasonable person to do so.

I hope you’re enjoying this letter so far. You can subscribe to make sure to catch every edition of The Constituent. It’s completely free!

Inelastic Demand and Gas Prices

Oil fits the oligopoly market failure description really well.

It is a finite natural resource that cannot be created, only extracted from where it already exists.

There isn’t really a good substitute for most of its uses.

Extraction is based on geography—if there are no oil reserves below where you’re standing, drilling doesn’t help.

It is an incredibly expensive and capital intensive industry because you have to prospect an oil reserve, acquire drilling equipment, pay extraction fees/taxes, pump and store it, and maybe even ship it.

Because of the expense it is dominated by a small number of really large firms.

Governments can regulate who can drill when and where based on their voters’ preferences.

In the current global reality, almost nobody can actually reduce their hydrocarbon use to zero.

All these things add up to make oil really inelastic. Even if gas prices get up to $6 per gallon, you will still buy gas. You might be a bit less, and be a little more careful about how/when you drive, but you can’t just not buy gas. In other countries, where public transportation isn’t just an afterthought mocked by ruling class, some people might actually be able to buy zero gas, but oil is still used for thousands of other things, and people in those countries aren’t gonna stop buying all of those things.

So, global consumption of oil is really stable. The only thing that really could lower the global consumption would be an event out of human control…like a pandemic.

Because consumption is so stable, and the market is so thoroughly dominated by just a few firms and organizations (like OPEC), oil producers can choose to produce less oil, and they will get a higher price for it. We will pay the higher prices because we are fairly dependent on oil. In the long term people can adjust their demand for oil, but this isn’t easy to do quickly. If we do adjust our demand down to the supply, we can get back to more normal gas prices.

But, oil producers aren’t really interested in producing more oil right now. Look at that graph. Production is several million barrels of oil per day below what it was before the pandemic.

This is what happens when markets are not competitive. Even aggressive antitrust enforcement here might not have a huge impact, since so much of the global market is not influenced by US regulation, but the economic concepts of monopolization still apply.

There are a small number of very powerful firms/countries/organizations that are producing oil, and anybody who wants to start a new firm to compete will have a really tough time doing so. So the market is dominated by a small group of firms (I’m just gonna use this term as a catch all) that are happy to keep production low, and make a huge profit.

This is part of the reason why there are over 9,000 approved production leases in the United States that oil companies are currently not using. The oil lobby says this statistic is misleading because it takes time to develop approved leases. But, as a general rule I’ve found it wise to always be cynical about what lobbying groups say. I don’t say that because I’m a cynic (I’ve been told I make cynicism seem like the minor leagues), I say that because even if we take the lobbyists at their word, the story still doesn’t add up.

If you are enjoying this letter and appreciate learning something new, help us grow.

Suppose it is true that these 9,000 untapped leases are going to be tapped as soon as they can be. How long will that take? For as long as we have been hearing about needing to increase domestic production, why haven’t these leases been under development already? This undercuts a major talking point from the oil lobby.

If it takes this long to get leases into operation, then the answer to lowering gas prices is not more domestic production—approving more leases right now apparently won’t lead to any new production for quite some time. By that time, whenever it is, other oil producing countries may be back up to producing at pre-pandemic levels. If they are, then oil prices will fall back well below $100 per barrel. At that price these wells must not be profitable, otherwise they would have already been in use.

This is the oil lobby doublespeak. Much of the hydrocarbon production in the United States is only profitable at higher oil prices. If companies produce more they increase supply, which lowers prices. So, approving new leases won’t, at least based on past behavior, lead to new production unless prices are high. But if more leasing sites are approved, and production is increased, prices won’t be high enough for oil companies to pay enormous dividends to their investors.

My general rule exists for a reason.

Even taking the oil lobby at their word it’s still hard to believe they don’t have a vested interest in keeping prices high. Plus, if you’ve been clicking on the links I’m throwing in, you’ve already seen oil executives say this outright.

In a more competitive market, where there are lots of smaller firms producing oil, the big firms cannot dictate supply so easily. These 9,000 leases would be operating, and the big firms wouldn’t be able to restrict production to keep prices high. These big firms would have to lower their prices because of the increased supply.

The only reason this isn’t happening is because oil creates a unique quasi market failure. Individually, prices are somewhat elastic, but the global economy is so dependent on oil that we really don’t change our demand quickly, or without massive changes in the market. As a result, the price of oil is highly inelastic as a whole. The supply cannot be substituted with something else, it cannot be created, and extraction is regulated. Creating a new company to compete is really expensive and difficult.

The end result is something that looks really similar to a market failure; not terribly different than if everybody’s kid had a genetic defect and they needed medication to stay alive.

Quick Final bit About War and Oil, and Gas Prices

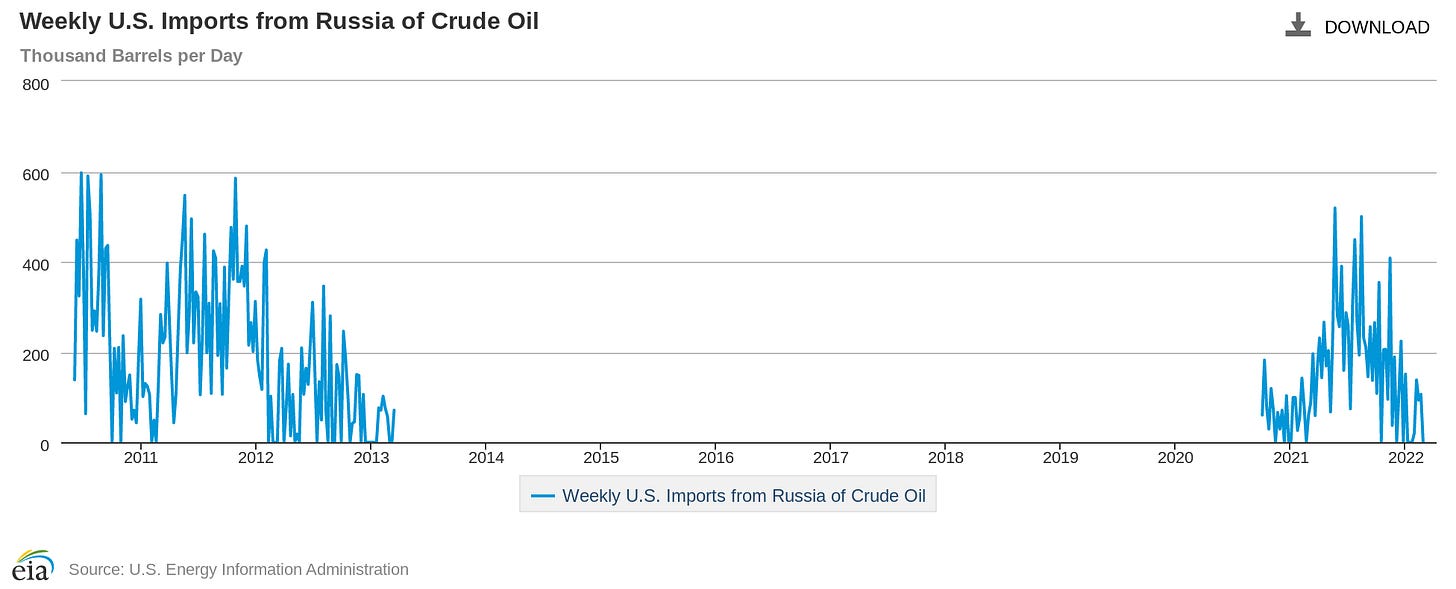

Right now prices are even higher than normal because of the war in Ukraine. Russia produces a lot of oil. President Biden only banned the import of Russian oil a couple hours ago. For the first couple of weeks of the war the US was still importing Russian oil. Our crude oil imports have been off and on for years, but most of what we import from Russia is unfinished oils—though I have to admit I don’t really know the difference.

If it seems odd that oil prices would have gone up without a ban on Russian oil, just think of oil like a stock you’d trade on the stock market. Oil is a commodity, and gets treated much like a stock. When Russia invaded Ukraine oil traders anticipated that some type of ban on Russian oil might happen. They hurried and bought up all the oil they could while prices were low—which made prices jump a lot because the demand for oil right this second went through the roof.

It’s hard to say, now that Russian oil imports have actually been banned in the US, if the price for oil will stay where it is or not. The increased demand in anticipation of this might have already set the market price to a new non-Russian normal. Or, the supply cut could end up being larger than the demand increase that happened in anticipation, which would make prices go up further. Or, if other countries (mostly thinking of China, Russia’s largest buyer) buy all the excess Russian oil, and the US and other Russia-banning countries just substitute other oil for Russian oil, the market would essentially not change, and prices should go back down to what they were before the war.

But, my Big League cynicism wouldn’t let me bet on that. As I’ve already laid out, oil companies have no interest in lower prices right now, and you can usually trust that a company with monopolistic market power won’t miss a chance to squeeze more profit from a crisis narrative.

Thanks for reading The Constituent. If you’d like to support the newsletter, here are a few options.

-Thanks,