On Friday, President Biden gave what I believe to be the most important speech by any president at least in my lifetime, and perhaps for decades longer than that. If you want to watch it, here it is:

But, the whole point can basically be summed up in one sentence: economic theory doesn’t work without competitive markets.

If that sounds familiar, it should. Anyone who knows me outside this newsletter has heard me say—probably several times—that free markets and competitive markets are not the same thing, and making this mistake has caused a lot of economic harm in the United States.

So let’s get nerdy. I’ll simplify it as much as I can.

The fundamental concept of all of economics is supply and demand. Wherever the cost-per-unit price is the same as the price people are willing to pay for a good or service, that is where the '“invisible hand” of the market sets the price. If a company charges more than that price, a competitor will form and offer the good or service at that price, and the company that was overcharging will either lower their prices, or go out of business.

Since about the 1980’s the United States has been trying to answer the question: so what happens if there are no competitors? Well, most often, the answer is that prices go up—and sometimes they go way up. Rather than make this letter a million words long, I’ll refer you to the work of Matt Stoller. He has made a career out of demonstrating the effects of anti-competitive actions from companies who do not face enough competition; effects that usually include massive price increases.

The non-mathy version of the economics goes like this.

The easiest route to profits in an economic market is to eliminate competition. If there is no competition you can actively make your product worse, and charge more for it because there is nowhere else for consumers to go.

Speaking completely hypothetically, if I were a social media company, and I could eliminate competition by buying my competitors then I could make my social media site toxic. I could design the algorithm to try to make people addicted to their feeds; I could flood feeds with so many ads it’s sometimes hard to see what people are actually posting; I could allow special interest groups to manipulate people, and even encourage manipulation because making users enraged or afraid will keep people coming back; I wouldn’t have to give a whit about the privacy of my users’ data because they have nowhere else to go for social media; and I could manipulate the price of advertising to eliminate other competition—like newspapers.

Good thing I’m only speaking hypothetically.

How does this sort of thing become possible? Chicago School economics.

Chicago School is a branch of economics that became dominant around the 1970s. It insists that markets entirely free of regulation will be the most competitive because people will always behave rationally, and therefore the freest market will always lead to the most competitive outcomes. It sounds great—if you think people are always rational. But if you think that, I’ve got a Qrazy Qonspiracy to tell you about.

I won’t get too deep into economic rationality here because it deserves books of its own, but all you really need to know is that people aren’t economically rational as described by the Chicago School. This has been proven many times over. Even when the definition of rationality is changed to something more realistic people still consistently fail to meet the threshold.

The United States used to have a fairly aggressive antitrust regime, but it all came crashing down in the 1980’s thanks, in large part, to Robert Bork. Bork worked as Solicitor General in the 1970s, then as a D.C. Circuit Court judge in the 1980s. His biggest claim to fame is taking a Chicago view of antitrust mainstream in the legal world. Rather than strengthening competition in markets, Bork and the Chicago economists argued that allowing big mergers often helped consumers because it increased consumer welfare.

Consumer Welfare

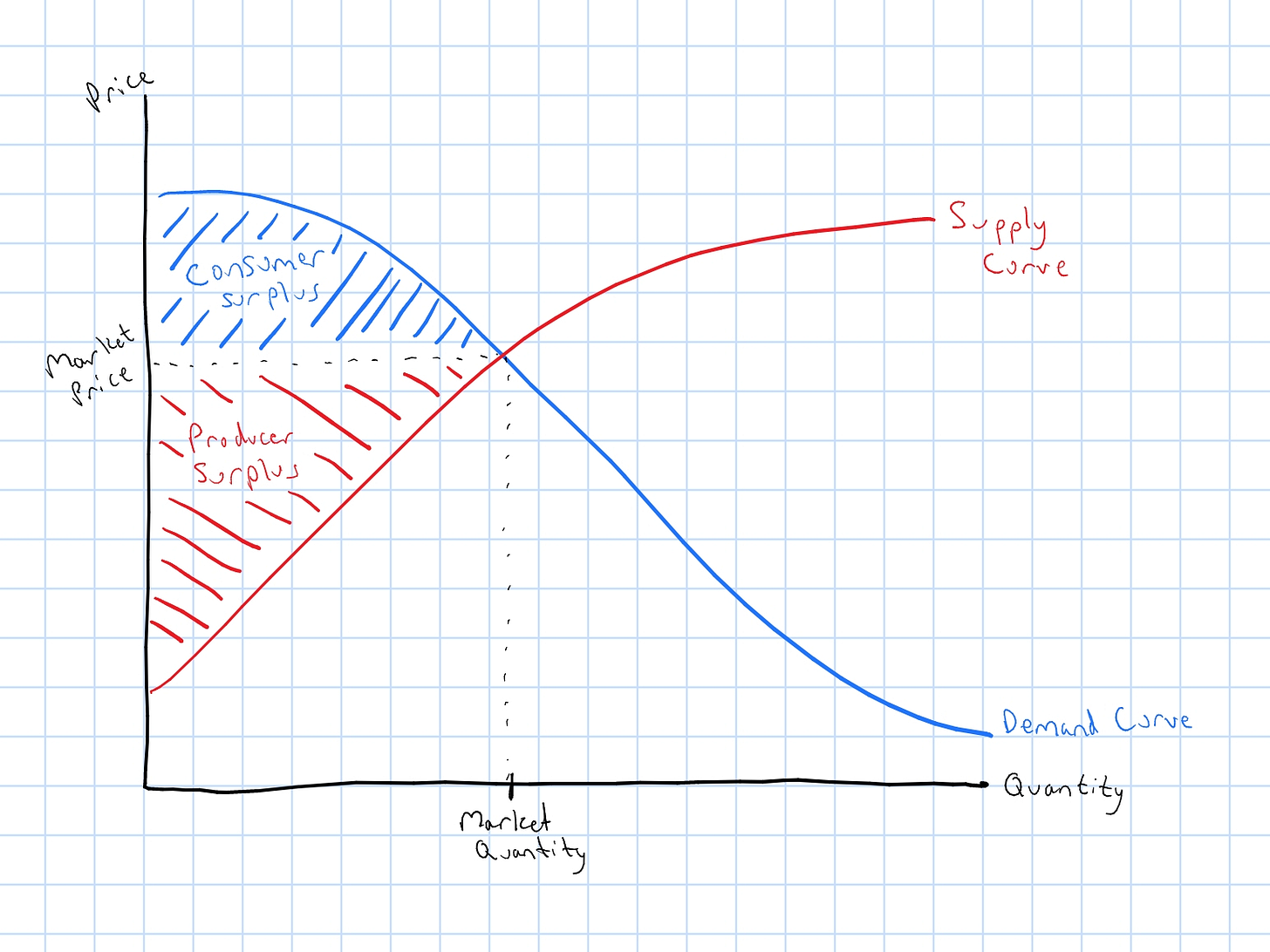

It’s dense, and unless your a hard core nerd like me, it’s probably boring. But it’s important to understanding where we are today. To help with this, I’ve drafted another soon-to-be million dollar NFT.

In this basic supply and demand graph the intersecting point is where the market will determine the price and quantity of a good or service. That’s basic stuff that, assuming a competitive market, will always be true. What matters here is the blue area called consumer surplus. It’s a very theoretical and difficult to measure concept, but the standard accepted definition is that consumer surplus is the economic gain to a consumer because they were willing to pay more for a good or a service than they actually had to pay.

The Bork approach was that anything leading to lower prices also must lead to more consumer surplus, and thus could not be anticompetitive. The modus operandi under the Chicago era antitrust framework was to allow just about any merger that companies wanted because the efficiency gains of the merged company would lead to lower prices. The error in this approach is that it is incredibly myopic. The short term outlook on consumer surplus has led to long term damage for several reasons.

The first is obvious to just about anyone who thinks people behave like people and not like numbers. If enough mergers are permitted then what is to stop companies from raising prices down the road, once they have stifled or bought out their competition?

The second reason this short term view of consumer surplus is harmful is that consumer surplus is not a real measurement. Quick, tell me what your consumer surplus was over the last 12 months? I’m an economist, and I don’t have the slightest clue what mine was, because this isn’t how people behave. People will generally buy a basic basket of goods to meet their essential needs. If they are middle class and have money left over after that they will determine their personal preference for saving and spending, then divide that additional spending into whatever categories they think make their life better off (Golf. The answer is golf).

Coming to an actual dollar value of consumer surplus requires each person knowing exactly what the current price are for all the goods and services they buy, and knowing what the lowest market price of all those goods and services might be, and also knowing exactly how they might spend any money that results from the difference of the two. Clearly, this is a theoretical measurement only.

But thinking of these things forces us to stumble on another flaw of consumer surplus: it is always changing based on the relative price of goods or services compared to other services. This means the actual price is not really what matters. Factor in the value of a good or service relative to the value of a dollar, and we get real abstract real fast.

The third reason this merger is harmful is because of what it can do to workers. If there are fewer companies, there is a less competitive labor market. Workers laid off because merged companies killed their competitors will flood the labor market with extra workers, allowing companies to bid down wages.

When these three things happen, the additional consumer surplus from the merger disappears.

I’ll use an example to help make this make more sense. If I can golf for $25, but would be willing to pay $35, my consumer surplus is $10. Now, if a golf course can buy a fertilizer producer, and a lawn equipment producer, and a water source, and really roll up all the costs of doing business into one company, they might be able to offer golf for $20. Bork would say the market is better off because my consumer surplus has grown from $10 to $15.

This is true, if the value of golf for me remains $35. But it might not, because the merger could cause the value of golf to change, or the value of the dollar to change.

This example will stretch itself a bit because golf is a localized market, but think about this example in terms of Walmart, Amazon, Facebook, or any other giant corporation, and you’ll understand my point.

Suppose now that the golf course owns the lawn and water supply, I have to pay more for water utilities, and the value of my home falls because my lawn dries up without enough water or fertilizer. Well, now I have to spend more money on water for both basic living and for my lawn in order to maintain my same standard of living. As a result, I might only be willing to pay $29 dollars for golf. Because of the merger, my consumer surplus for golf has fallen because the value of my dollar has fallen: it now buys me less water and home value per dollar than before the merger.

But it gets worse. Now that the golf course owns the supply of all the resources needed to run a golf course, they can charge other golf courses more. A few golf courses might be lucky enough to cover those costs, and a few might have the capital to start their own fertilizer and lawn equipment branches. But, even if they are lucky enough, they will have to charge more for a round of golf to pay off the costs of starting these companies. So, the merged golf course is now the cheapest place to play by far. This leads to the course always being packed with golfers. Because the course is so packed, the course no longer needs to worry as much about upkeep of the course—why spend that much money when there is already a waiting line for tee times?

Well, waiting around while playing golf sucks. It’s not fun to sit and watch other people who are not good golfers hit their terrible shots while I stand and wait to hit my own terrible shot because they are in the way. So the price I am willing to pay for golf goes down. Since upkeep on the golf course is no longer a priority, the price I am willing to pay goes down further. Now I might be willing to pay $23 per round. With the price of golf lowered to $20 per round, my consumer surplus has actually shrunk from $10 to $3 because of the merger.

These knock on effects happen because the merger has changed the price of goods and services relative to one another, and to the value of the dollar. Bork didn’t anticipate these downstream effects. He saw that consumer surplus might grow initially, and ended the thought experiment there.

But, the damage keeps piling up.

If other courses have to close because of the merger, and this course laxes in its upkeep, there will simply be fewer greenskeepers needed at golf courses. Some will have to be laid off. Having little, if any, experience in other industries, these greenskeepers might not make as much money in a new job. The greens keepers that do stay might have to agree to a pay cut (or forgo a portion of their raises in the future) so they can keep their job. Because other industries can now hire former greenskeepers at a lower wage, all job applicants will have to accept a lower wage because the market wage has shifted downward due to the influx of former greenskeepers to the labor market. Anyone who really wants to be a greenskeeper now has to accept whatever wage the merged course is willing to pay.

Because of this the actual value of wages falls. Workers have less spending power. This has actually happened in the real world, and it may be the root cause of much of the racial and political resentment we see growing around us. Now, because the value of my wage is smaller, I might only be willing to pay $21 for golf. My consumer surplus is almost entirely eliminated, and for someone who doesn’t love golf as much as me, they might play far less golf, which makes them worse off too.

The bottom line is that mergers hurt competition, which hurts economic markets.

We Should Have Seen This Coming

We should have known a long time ago—long enough ago to have changed course in the 1980s—that the Chicago School framework wasn’t one that would lead to real world success. We actually had a real world experiment. About the time Bork was cutting his teeth in Chicago antitrust theory, a group of Chilean economists known as the “Chicago Boys” convinced a military dictator to go full Chicago with the economy in Chile. The were trained to design the markets directly by the Chicago School itself. The result was massive monopolization of their economy, the poor and middle class were left far worse off, and this led to a massive economic recession with unemployment near 25 percent.

I am shortening and simplifying the story somewhat, because you’ve probably had enough economics for one day. But the core issue is that the Chicago School relied too much on economic theory, and not enough on empirical evaluation of the way people actually behave. Now that we have amazing computers, it’s far easier to analyze real effects, and not rely on a theory that assumes people are all rational.

To be fair, I have to tell you that anti-government regulation types will argue that the Chicago Boys never actually tried real Chicago economics in Chile, and that’s why it didn’t work. My response to these people is the same as my response to leftists who argue that Stalin never tried real communism: I hope no country ever does.

The flood of mergers made Chile worse off, and it has made the United States worse off. Other countries have maintained more pro-competition regulation of big (often American) companies, and their markets are more competitive than our own. Moving up the income ladder in the United States is now less likely than in other developed nations. For the first time in modern history, a generation of Americans is worse off than their parents.

A completely free market doesn’t lead to competitive outcomes. It will naturally lead to monopolies. When a huge corporation can force the decisions of their suppliers, or manipulate prices at which their clients sell goods, it becomes much harder for a new company to compete. This barrier to entry leads to less competition, not more. The United States became so lax in their enforcement of competition, that they allowed Boeing—the US airline manufacturing monopoly—to do its own safety tests. You may have heard about a faulty sensor that caused a few crashes.

When a company’s primary concern is shareholder value the arch of corporate governance will quickly bend toward increasing their market share, not creating a more competitive market, where they can lose market share to competition.

So, the best economic outcomes stem from a competitive market, which is not the same thing as a free market. The argument President Biden made on Friday is the same one I’ve been making to you for years. It’s really simple:

Free markets are not the same thing as competitive markets.

Capitalist economic theory depends on the preexisting condition of competitive markets.

Thus, the role of government is the ensure markets are competitive.

This is how we get to more economic success.

How Did Young Americans Come to Love Socialism?

One more observation.

But this has been long and dense, so I’ll make it quick.

The failure of the US government to ensure a pro-competitive market structure is what has directly led to the love of “socialism” among young Americans. The links above should make it pretty clear that Americans born after about 1980 have gotten screwed by the monopolization—let’s call it the Borking—of the United States.

Capitalist theory relies on competitive markets, which we haven’t had for some time.

But, we apply the capitalist label to our oligopoly.

Young Americans looked at this oligopoly and thought, “Man, this blows.” And they were right. But they erroneously thought that what they were looking at was capitalism, because this is how we labeled it. So they decided it was capitalism that sucked—erroneously.

They then looked at Europe—where there is more capitalism than in the United States—and thought, “Man, I want that!” But they erroneously called it socialism because the United States also Borked the definition of socialism. Nobody who is serious was looking at true socialism and asking for that. But in the United States a racialized history of taxation has led to us insisting that any attempt to quell market failures—something that are basic to economic theory, but that’s another letter for another time—must be socialism. This isn’t true, and Heather Cox Richardson does a marvelous job of tracing this back to former slave owners not wanting to pay taxes for things like schools and roads for freed slaves. The label of socialism stuck, and now it is used to describe any attempt to cure a natural market failure.

Europe has done a better job addressing market failures than the United States—though not a perfect job. This is why, if you listened closely enough to the specifics of what young Americans have been asking for—rather than just the label that has been attached to it—it becomes clear very quickly that young Americans have actually been asking for more capitalism.

I was getting ready to write another book entirely about this subject, but the recent shift back toward capitalist competition in the United States might make the point moot. So, I may move on to something else.

Either way, I hope Biden, and any other successive elected official from either party, is successful in making US markets more competitive. Let’s Un-Bork America Great Again.

Thanks for reading The Constituent. If you’d like to support the newsletter, here are a few options.

-Thanks,